There are often moments in our lives that mould us in some way. A defining day, hour, or minute that changes our perspective of the world. For me, my 2025 trip to Pakistan was such a moment: a defining lesson, one that I believe the world should know about.

Eight months ago, I was deeply entrenched in right-wing politics. Now, I sit with refugees from Afghanistan — a country ruled by one of the most sadistic regimes to have gained political power in the past 75 years.

While I wish I could have spent time interviewing every refugee I came into contact with, I had decided prior to my arrival to focus solely on Afghan women. My reasoning? Project refinement. I needed to utilise my time as efficiently as possible in order to maximise productivity.

Statistically, women are more likely to experience severe hardships than men — often stemming from cultural traditions and gender-based discrimination, particularly in countries governed by religious authoritarian regimes, such as the Taliban.

Had I more time and experience, I would have liked to gain a more balanced understanding of the crisis by interviewing men, and if supported by security, the Taliban themselves.

I have been fortunate enough to interview some incredible people in my journalistic career, but no stories have come close to the horrors these women have had to endure.

A little context.

Let’s go back a little, before delving into what I’ve learnt over the past ten days.

For those who don’t know, the Taliban — which ironically means “students” in Pashto — are a group of radical extremist Islamists based in (and around) Afghanistan.

Their history is short, bloody, and filled with unspeakable crimes against humanity — crimes that my interviewees, their families, and friends were subjected to on a daily basis under their illegitimate rule.

In 2001, America and her allies invaded Afghanistan in an attempt to bring democratic procedures and stability to the nation.

It should be added here that this is a very brief synopsis. If you wish to understand the history of Afghanistan in greater detail, I encourage you to research extensively — it is a fascinating subject.

After 20 years of American supervision, international financial support, and relative prosperity, the United States, under Joe Biden’s leadership, decided it was time to withdraw.

This led to one of the most catastrophic military evacuations in history. Within 48 hours of the last American aircraft leaving Kabul, the Taliban had retaken the entire country with very little resistance.

What’s worse, many refugees here in Pakistan suggest that America knew this would happen — and allowed it to unfold without intervention.

America spent $2.3 trillion in Afghanistan, spent 20 years on the ground, and managed to maintain a degree of national safety. Yet within just 48 hours, the country fell to the Taliban, whose numbers and ferocity had been growing as America’s presence diminished.

This triggered a mass evacuation of Afghans. Although the numbers are debated, between 1.3 and 3 million fled to Pakistan, 1 to 6 million to Iran, and countless others scattered across the globe.

2025.

Pakistan and Iran have begun the mass deportation of Afghan refugees, sparking fear, hopelessness — and a pressing debate: is the forced return of Afghans an act of complicity in genocide?

Genocide is a term being used increasingly — perhaps justifiably so. Its definition: the deliberate and systematic destruction of a national, ethnic, racial, or religious group.

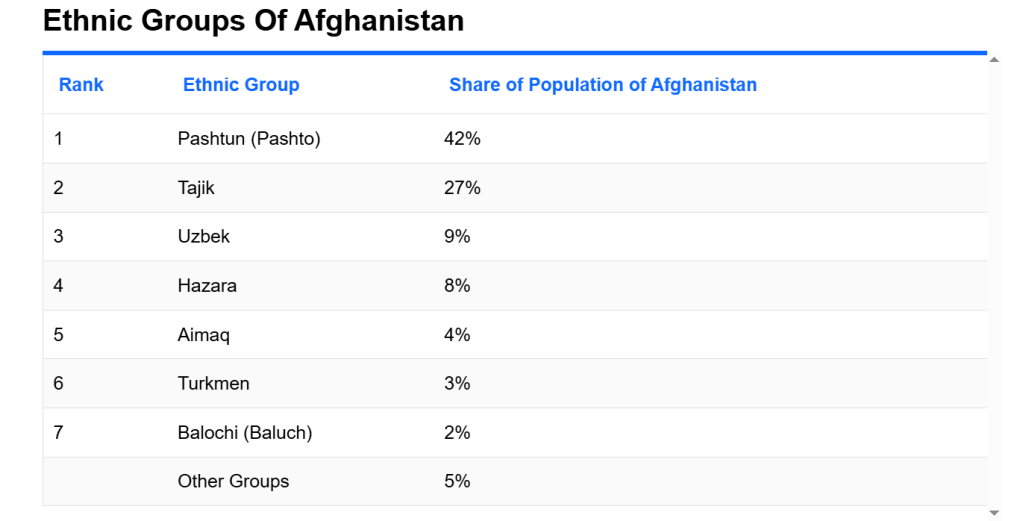

In Afghanistan, there are several ethnic groups and two major religious communities.

Evidence gathered from my interviews, alongside information available online, in the media, and in historical records, shows that marginalised groups in Afghanistan are being systematically targeted by the Taliban — killed, maimed, tortured, and raped — in what appears to be an attempt to erase the Hazara people.

Of the ten interviews I conducted, half were with Hazara individuals. Of those, every single one had either been subjected to hate-driven terror or had witnessed violent attacks against their community by the Taliban.

This raises a critical question: is deportation back to Afghanistan an act of complicity by other nations?

Beyond genocide, torture, murder, rape, and the countless other crimes committed by this monstrous group of Islamic extremists, the Taliban have enforced inhumane laws on women and girls. These include:

The enforcement of child marriage

The mandatory wearing of the burka by law

A complete ban on education and employment for women

Legal enforcement of public silence

Prohibiting women from leaving the home without a male guardian

10 days, 10 interviews.

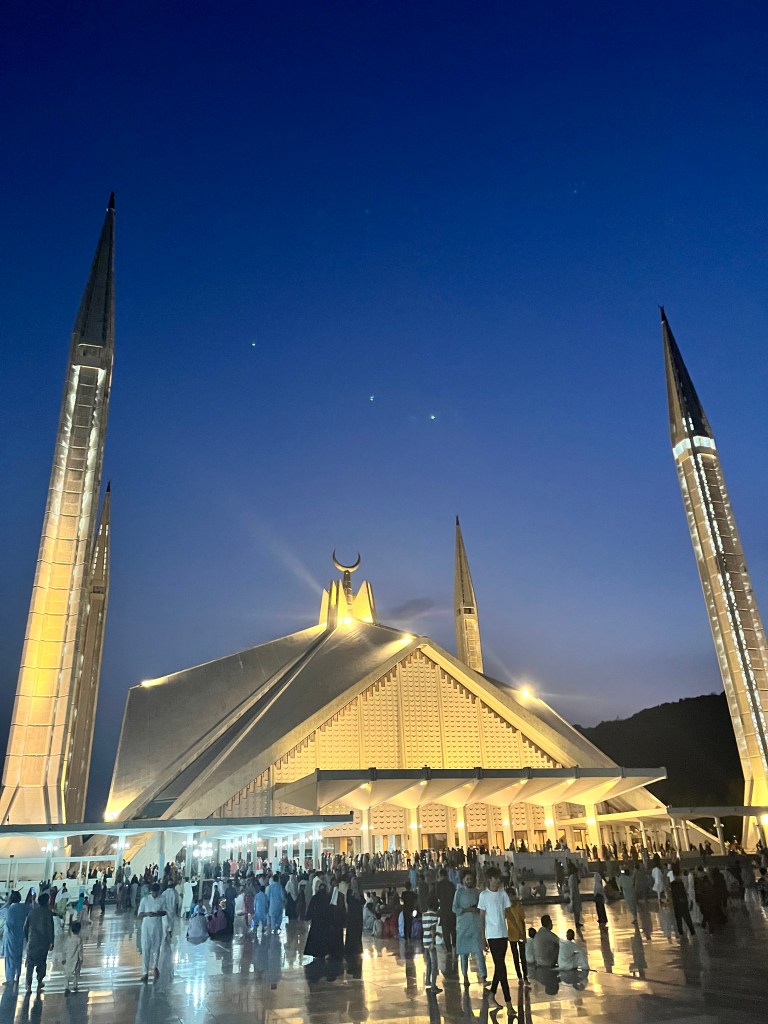

I have lived in Islamabad for the past ten days, moving from Airbnb to Airbnb.

During this time, I conducted interviews with ten Afghan women — all of whom experienced life in Afghanistan both before and after the Taliban takeover in 2021.

Their bond stretches beyond nationalism, religion, or ethnicity. Their sisterhood has grown from shared abuse, oppression, and neglect at the hands of a terrorist organisation masquerading as an illegitimate government.

Each interview taught me more about the dreadful lives of refugees. Though they have each other, they live in constant fear — fear of deportation, of being discovered, of facing further torment.

I’d sit and speak with them at length — sometimes for hours — occasionally in formal interview settings, other times around their homes, sharing meals. Their hospitality is immeasurable, and their strength remarkable, yet the reality of their situation reveals itself in long, silent stares into nothingness.

A mother holds her son, her eyes fixed on a loose thread in the rug. Her mind races with fears and horrors we can only imagine. Her son — thin and clothed in the best they can manage — clings to her quietly.

Another woman stares deeply into space, shaken by a question that returns her to a time before all of this — a time when she was running freely through the streets of Kabul, before she was tortured, before she was maimed.

There is a silence that falls over them like the waves of a dark ocean — an ocean made of trauma and fear. Occasionally, there are breaks in the tide: moments of happiness, clarity, and brief peace. A reminder that they are no longer in Afghanistan. That they are miles away from its borders. That they are surrounded by their friends, their families. Then the waves return — that long, foreboding dread.

What if they come tonight?

Where will we go?

What will they do to us?

What about my children? My sister? My brother?

I found, in those moments of silence, a bridge.

While we in the UK — and across Europe — struggle with the debate around high migration numbers, both legal and illegal, here in a small, modest home thousands of miles away, the noise of ideologies fades. I no longer see “a Muslim” or “an Afghan.” I see mothers, sisters, and wives clinging to hope — to dreams — praying that someone, somewhere, will help them.

Tears were common among the interviewees. At times, I had to leave the room so the interviewee and my translator (herself an Afghan refugee) could speak alone and comfort one another.

I always made sure to pause — to offer them water and tissues, to comfort them appropriately, and to ask if they wanted to continue or stop. Not a single refugee wanted to stop. They wanted their stories to be heard — to be told. I even found myself welling up on more than one occasion.

You are taught a lot about interview techniques in journalism. I’ve read three books on the subject. But no amount of training or reading can numb your humanity.

My questions varied from interview to interview, although there were key themes each one explored. And every story came to the same conclusion: the Taliban are oppressing their people through violence, rape, and forced marriages.

Hospitality.

Hospitality is no joke to South Asians. There is a way — a tradition — and they stick to it without apology.

When I conducted my first interview, it was with my translator. She brought me flowers and a gift for my girlfriend back home. She greeted me with, “Salam alaikum” (peace be upon you), to which I attempted — and failed — the customary response: “Wa alaikum assalam” (and upon you be peace).

We spoke for hours — about her childhood, her experiences with the Taliban, her family, her life here in Pakistan, her dreams, and the future she hopes for Afghanistan.

A few days later, I was taken on a nine-hour journey through the mountains of Murree by a family whose daughter I had interviewed regarding feminism and sports in Pakistan. They paid for everything — fuel, tolls, drinks, snacks — and, of course, extended an invitation to dine at their home the following day (an offer I regretfully had to decline due to other commitments).

After one particularly emotional interview, one of the refugees invited me to her home for an authentic Afghan experience. She cooked a vast meal, offering a generous spread of traditional dishes. That evening was filled with laughter, joy, and a rare sense of peace between us.

In return, all they asked was that I share their stories.

I was catered to like a king. When I offered to help clean up after the meal, I was quickly and firmly told, “No, no, this is not our way — we do this.”

I said, “In the UK, we don’t have this level of hospitality. We rarely invite strangers into our homes, let alone serve them such delicious food.”

They replied, “This is the Afghan way — this is normal to us.”

At no point during the meal did I feel there was any ulterior motive. I’ve travelled to many countries where hospitality is offered — only to later be met with requests for money or favours.

There was no such trap here. Only the grace and generosity of the Afghan people.

What am i going to do with all these Interviews?

Firstly, I need to transcribe and organise the interviews. Once this is done, I’ll begin the search for a media outlet willing to publish the stories I’ve written — which is, admittedly, the hardest part.

Following publication, I’ll begin writing the full stories. This includes emailing officials, gathering statements from public figures, charities, the UN, and any other organisations that can help bring these stories to light and push them forward.

After completing this stage, I plan to write a book — a historical memoir dedicated to each of the women I interviewed, ensuring their voices are remembered for as long as we continue to read.

Each chapter will focus on the life of one woman. I plan to include twelve chapters in total: ten based on interviews conducted during this trip, and two based on upcoming interviews I’ll conduct online.

I want this book to be a masterclass in writing, with original artwork created by one of the refugees.

Naturally, a percentage of all book sales will go towards supporting the women who shared their stories — either directly or through a charity that aids Afghan refugees.

I do have a time line for the release of the media pieces, I’d like them picked up and published before the end of this month. However, I plan for the book to be completed within the next two years, and I hope published by 2028.

Meanwhile, I will be publishing profiles of the refugees on Uncharted Thoughts. Much like “The Bravest women on earth – interviews with the women of Afghanistan” published last month. I plan on releasing each refugees story on a monthly basis until all are complete. This will act as a miniature version of the books chapters.

Please consider subscribing for more content. Each month I release a News Letter for my subscribers.

Trips conclusion.

Afghanistan is a tragedy beyond most people’s comprehension. Its citizens are held captive by their overlords — a group of zealot gangsters who rape, murder, and pillage in the name of a God they so clearly do not represent. They use Islam as a cloak to justify crimes against humanity, twisting the words of the Qur’an in pursuit of power and wealth.

The people of Afghanistan are not aligned with the Taliban — they are simply silenced by violence and fear.

The international community is not doing enough to support refugees in this part of the world. The ongoing deportations by Pakistan and Iran will have dramatic and devastating consequences.

Of course, Afghanistan is a sovereign nation. When I asked whether Afghans wanted Western intervention, the response was often: “The world needs to apply pressure on the Taliban and must not allow them to be legitimised by the international community.”

This leaves the world in a form of geopolitical checkmate. While military intervention by Western powers is often condemned, diplomatic pressure on authoritarian regimes frequently backfires — with the most vulnerable civilians suffering the effects: starvation, water scarcity, disease, and exploitation.

This trip has taught me much about people, power, and belief. Religious authoritarianism often corrupts the very texts it claims to draw wisdom from. The separation of religion and state — alongside common law — remains the clearest path forward for any civilisation that seeks justice and progress.

Militia and terror groups are often propped up by states seeking to create regional instability. Though I have much more research to do, it is evident that the United States, Saudi Arabia, India, and Russia have all, in different ways, contributed to the Taliban’s rise. If the international community truly wished to end Taliban rule, it could do so within six months.

Refugees live in poor conditions. Their lives are dictated by unseen powers — reduced to pawns in the political games of distant nations. They are exploited to rally voter support, yet rarely offered real security or dignity.

Finally, the United Nations and its list of Universal Human Rights has failed to gain meaningful traction. Since the Second World War, the rules set out by the UN have struggled to survive the harsh realities of the 21st century. This is largely because the UN lacks true power — it cannot enforce its will on states such as Afghanistan. A peacekeeping body that refuses to protect the innocent is a force without real-world authority.

To defend the voiceless, we must do more than speak. We must seek justice — and hold aggressors to account.

Leave a comment